Confronting "hard truths"

A Q&A with Rebecca Clarren on excavating painful histories, both as an insider and an outsider

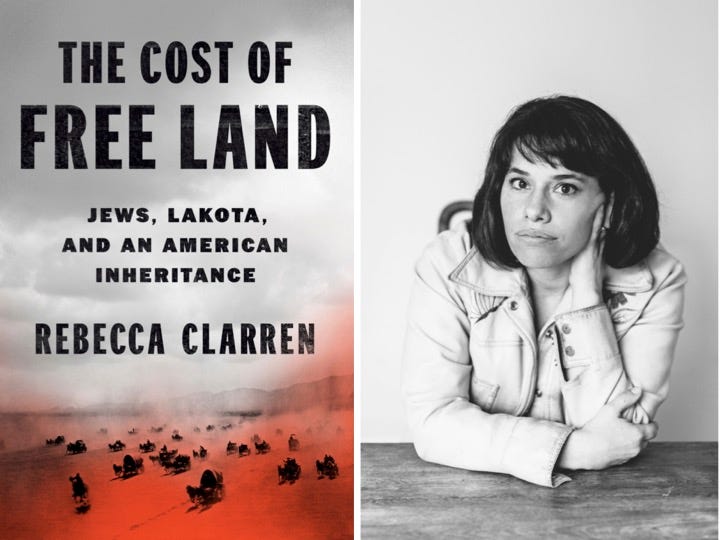

This week, I’m truly thrilled to share a Q&A with my friend Rebecca Clarren. Her new book, The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance (Viking/Penguin) is a moving and masterfully researched story about the connections between her Jewish immigrant family’s life on a South Dakota homestead and the dispossession and oppression of the Lakota people. You can get it wherever you buy books—and I highly recommend that you do. It’s totally absorbing.

In the conversation below, which I couldn’t bring myself to condense, we discuss the challenges and responsibilities of reporting on Indigenous communities and why—yes—you should turn every page.

What was it like to research your own family history? How did it feel different than your normal journalistic research process?

It was both incredibly difficult and gratifying. I’ve spent so much of my career, pretending that who I was and where I come from has no bearing on my reporting. And while I do really think there are times when it’s not valuable to insert oneself into a reported work, in this case, when the issues I was reporting on were so connected to me personally, it’s been a relief to be transparent. Weaving in my own family story and my own perspective has made me feel far more vulnerable, but I hope that’s meant I’ve worked twice as hard on this as on anything I’ve ever done before.

The other half of the book is about the dispossession and oppression of the Lakota. How did you go about researching that piece? I’m particularly interested in how you worked around the fact that, so often, Indigenous history is written by white scholars.

I found a trove of oral histories housed at the University of South Dakota with interviews that were done with Lakota people in the 20th century. I’m really grateful to the university because they provided me with an hour of one of their graduate student’s time every week to help me search through the archives for relevant oral histories. These really helped me sidestep that reality that you mention of so much Indigenous history being written by white scholars.

In addition, there was a book written in the 1930’s about Joseph White Bull, the ancestor of one of the main Lakota sources in my book. I spent about a week reading the author’s original notes that formed the basis for the book. I also relied on Josephine Waggoner, a Hunkpapa Lakota who interviewed Lakota elders in the early 1900s. Her books were an incredible asset to me in my reporting.

Finally, I looked into the Congressional record and even old newspapers to search for testimony provided by Lakota. And on my travels in the Dakotas, I visited little local history museums and a number of tribal colleges with wonderful libraries. I found so many wonderful self-published local histories full of gems of information.

I was floored when I read that the oral histories you used contained accounts from both survivors and soldiers of the massacre at Wounded Knee, and that, as far as the director of the project knew, they had never been written about before. What was it like to find these stories and incorporate them into the book?

It felt very exciting because the thing that I have wanted so much to convey in this book was hard truths told with limited hand-wringing and emotion. Even though it’s somewhat memoir-y and voice-y, I tried to really step back from the page in those places so that there’s lots of room for readers to feel their own feelings there. Because, as a reader, I don’t like it when I’m told how to feel.

And so, it was exciting that there was such power in the language of the oral histories. It’s very upsetting and shocking, particularly what these seven cavalry soldiers reported about was being said by their comrades. I was very grateful to have their direct language to use, instead of conjecture. And guess I just feel such a sense of injustice that, to this day, there are these medals of honor that have been given out to those soldiers.

It’s wrenching. They really convey the true horror of the event. Which brings me to my next question:

It can be really hard to responsibly report on Indigenous communities as an outsider, as you know from decades of covering Indian Country. Sometimes, there’s a sense that it is not your place to tell particular stories. In this book, it’s really clear that you’re writing about Indigenous history as it intersects directly with your own. But I’m curious how you’ve grappled with your role as white person reporting on Indigenous affairs.

I have thought about this a lot. When I wrote a series of stories that ran in The Nation and Indian Country Today in 2017 and 2018, we had an advisory board of Native thought leaders—some of them had been journalists—who helped us do that series with a lot of nuance and context. And many of those people told me, ‘you are a good reporter and you should keep reporting.’ It wasn’t like, ‘you’re an outsider and we don’t want you.’ They also said to me, ‘listen, there are more than 570 federally recognized tribes in America, and if I’m Hopi and reporting on the Lummi Nation, I’m still an outsider in that community, on some level.’

So, I think there is something very powerful about reporting by someone who is from within the community. And also, I feel like what I did—and what I would hope other people do if you are an outsider—is that you just take great care. And the way I took great care was to do things differently than, let’s say, the way I did things at the beginning of my career.

Like what?

Before I visited Lakota elders, I spoke to people who I knew and trusted who are also from that community who could tell me, ‘here’s what’s culturally appropriate.’ Like, show up with groceries. That’s OK. In fact, that’s a culturally appropriate thing to do.

I also wasn’t sure if Penguin would be paying for any kind of sensitivity readers. So I actually used some of the money I got from the Whiting Grant to hire two different Lakota sources to read the entire manuscript to make sure I wasn’t out of bounds in any way. And I did the same thing with Jewish scholars. And what was so interesting was that the Native people were like, ‘you’ve totally nailed it.’ And the Jews were like, ‘um, I think you have a little internalized anti-Semitism.’ It was fascinating. This book was meant to be a corrective, but I needed to actually extend more context and nuance as a means of compassion to my own people, than I had in my earliest draft.

That’s so interesting!

In the end, Penguin did hire an Indigenous editor who read the book. Which is all to say, this takes a lot of time and resources, and I get it that if you are a daily reporter meeting a deadline or even a magazine journalist, this is all very hard to do. But to me, it was very important, and I’m very grateful it was important to my editor and her team at Penguin/Viking. And I hope it made the book feel OK.

It really comes through.

The other thing was, traditionally, journalists are taught never show anything to anyone you are writing about until after it comes out. But in this case, it was so personal and I thought so much about who owns another person’s story, that I actually showed the book to several people. I printed the entire manuscript out and brought it to my Aunt Etta, and also had an extra copy I shared with daughters. Similarly, I read the entire book aloud over the phone to Doug White Bull over a period of two weeks, because he’s blind and he couldn’t read it. I wanted to make sure there wasn’t anything inaccurate.

If people wanted me to change something that wasn’t a fact, then it was a series of pretty hard but very important conversations. But for the most part, those were conversations I was having within my own family, not Native people saying, ‘I’m uncomfortable because this is making me look bad.’ I’m sure there are ways I could have done better. But I did really try.

You can really tell. Ok, last question: what’s one piece of advice you’d give others about book research in general?

In The New Yorker, the biographer Robert Caro wrote that you have to turn every page. I was haunted by that, because I was sitting on such a trove of original research. But I really did try to read every page and read so many books. So much of this book was filling in the white space around the edges of the story that I thought I knew. And so it was important for me to know as much what was out there as what wasn’t out there.

For example, it was really powerful to not just read Warpath—the book about Joseph White Bull—but the original notes that Stanley Vestal had taken that were the foundation of that book. They were available online, and to read every page of those notes—it was so insightful. In some cases, what was in the notes was not what was in the final book. And I often used the notes instead of the book.

So, I’m sorry to say that I think that Caro’s advice is the best advice.

I’m sorry too!! I thought you were going to say it’s BS so you can just get on with it. As I’ve written here before, I feel really frustrated that I just can’t read everything right now in my life. Did you run up against any hard limits?

You have to remember that a book is a marathon, and you might not get it in the first pass. I remember feeling that way initially. There was a certain chapter I wrote where I did this very stupid, ambitious thing where I was trying to take three major events in Native American history, all of which individually have entire books written about them, and I was trying to entangle them in one chapter. And I would just say, be kind to yourself.

Read enough that you know what you think you want to do with a chapter, and then start writing it. Just remember to make notes to yourself, like, ‘I gotta come back later and read this book, or this report.’ And then you layer it in. Because I did feel that desperate sense of, ‘oh my god, there’s just so much there.’ But you can know enough to then start to shape that narrative. And it does get easier and you can get to things later in the second round.

That makes sense. You get the general story down, and then you can focus your deep research more tightly.

Exactly.

Thank you, Becca! This has been so wonderful.

Again—I can’t recommend The Cost of Free Land enough. Find it here.