Making space for serendipity

A Q&A with Madeline Ostrander on creativity in the research process, and so much more

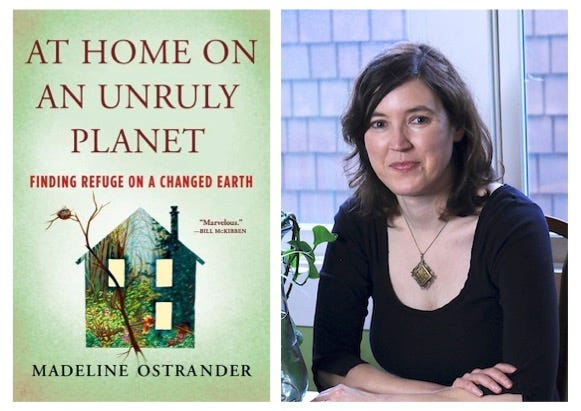

This week, I’m delighted to share a conversation with my friend Madeline Ostrander about the process of researching her wonderful book, At Home on an Unruly Planet (Henry Holt and Co.). Part front-line reportage, part rumination on the meaning of home, it is a book about climate change, grief, resilience, community, justice, and hope. It’s a great read for book clubs, university classes, and anyone trying to make sense of our current moment of upheaval. And it comes out in paperback on August 8 (aka today!). Get yourself a copy here.

In this Q&A, which has been edited for clarity, Madeline and I talk about the challenges of finding material that speaks to big subjects, keeping track of narrative details, and leaving space for serendipity. Enjoy!

What did researching this book look like?

I researched the book for about a decade. It began when I was an editor at YES! Magazine researching an issue on resilience. I was asking very broad topical questions and meeting with sources in the environmental justice community to get a big-picture understanding of their approach to things. They looked at climate change as a problem that would affect them at home—not a story about ice melting far away. That seemed like such an important perspective. I wanted to write stories that would help others understand the issue in this way. So I started “gathering string,” as journalists say—looking for more examples of activists and communities whose motivations for acting on climate change also tapped into feelings about home.

Once the book was under contract, much of my research was still conventionally journalistic, as in, a lot of interviews and a lot of document sources like scientific journal articles. But I also allowed myself to follow particular intuitions and explore the subject matter in non-linear ways. I spent a lot of time wading through the psychological and sociological literature on place attachment and displacement. I searched for the ways that anthropologists and sociologists name and categorize home. I also turned to more literary and philosophical reflections on home.

For instance, I came across bell hooks’ book Belonging when I was searching for literature on place. And as I wrote one of my more essayistic chapters, I wove together some of hooks’ reflections on home and community with research on NIMBYism, place attachment, and disaster response and preparedness. Connecting all of those different subjects and ideas became a very imaginative and even playful process for me in the research and on the page.

How did your research influence the structure of the book, and vice versa?

The book has four braided narratives and four essayistic chapters—and because of that narrative complexity, I needed the structure to be clear so that readers could effortlessly find their way through the stories. It’s a two-act structure. In the first half of the book, a community and a set of characters (as in real-life people whose stories I’m recounting) realize we are facing a new world with new threats. They encounter a crisis—such as a major wildfire or hurricane. In the second half of the book, they find solutions and strategies for coping with and recovering from these crises.

In both the narrative and the essay sections, I looked for protagonists who could carry readers on a journey through particular ideas that might help people cope. For instance, bell hooks became the lead character in a chapter on finding a sense of place in an era of climate crisis. Smithsonian Institution paleoanthropologist Rick Potts—who studied the concept of "home base" in early humans—became the protagonist of an essay-style chapter on how we understand the fundamental meaning of home. And in the wildfire chapters, I followed the stories of people like Carlene Anders—a small-town mayor and firefighter who led her community through the process of disaster recovery after a series of major wildfires.

The problems and challenges the characters wrestled with became the organizing force of the book and defined what I needed to research. For instance, what did I need to know about fire behavior or disaster recovery to explain Carlene’s story?

What was the hardest part of researching this book?

Because the book covered decades of experiences in some of the communities and research across many disciplines, I had to figure out how to organize massive amounts of research and interviews and notes. I found it especially helpful in the narrative sections of the book to draw up big chronologies.

For the section set in Newtok, Alaska, for example, I had, in effect, gathered pieces of oral history during my interviews—insights and descriptions and memories of what the community looked like in the past and how it changed over time. They were scattered across multiple notebooks, so I retyped my notes into a long document and organized them in a historical sequence. Then I indexed my notebooks, page by page. That way I could build a description of change over time from multiple sources, which made it much easier to write the narrative chapters. I could more clearly see the arc of the change, which then formed the narrative plot.

Your scenes are so vivid and evocative. What kind of research did you do to achieve that level of detail?

Narrative writing—especially longform—requires that you immerse yourself in the details. It involves a lot of tedious documentation and even more tedious fact-checking. I used photographs to write and then again to verify descriptions of scenes and people. I worked with my sources to reconstruct scenes, asking them for sensory details like the color of their house, what they could see out the window, what they heard when a fire was burning—anything vivid that could help recreate the experience. Then during fact-checking I called my sources back and walked them through every tiny detail, from what kind of plant was growing next to a house to where they were standing in a particular moment to technical information about, for instance, how fire moves across a landscape.

As I pulled all of these stories and notes and images together, I found myself awash in the experiences and the details. It was often much more emotional than writing a magazine story. I felt like I had lived through crises with my sources, at least vicariously. I had less distance between their feelings and my own. I felt a piece of the overwhelm of losing a home or living through a disaster, and I had to figure out how to manage those emotions while writing—when to channel them into the language and when to step back.

Wow, that sounds intense. And difficult. What was the most fun part of researching the book?

I love how book-writing allows you to spread out on the page and tell a fuller version of the story than you might in a feature article. I felt like my creative instincts could unfurl, and I could make interesting and unusual connections between issues and ideas—connections that I wouldn't be able to do in a smaller space and with less time.

I always feel it is an incredible privilege and honor when sources open up and share their personal stories—especially their moments of vulnerability—and trust me as a journalist to render them on a page. I take that trust very seriously as a writer, and I devote a lot of energy to making sure I convey these stories with truthfulness, respect, and empathy. When interviews are part of your research, this is also a huge component of the process—figuring out how to sensitively and respectfully document and then write about the experience of others.

Do you have any research advice for other writers?

It’s important to create room for serendipity and the subconscious in the research process. Especially since the pandemic, we've come to rely even more heavily on what we can find online—and I think that can constrain us more than we realize. A big piece of research is just opening yourself up to curiosity and seeing where it takes you. If you allow yourself to wander, to get lost a little, to stumble on things, to ask weird questions, that can lead to some of the best ideas.

In researching this book, I let myself meander through literature that had indirect connections to what I was writing but could turn up surprising insights. I ventured back into The Grapes of Wrath and Steinbeck’s reflections on migration after environmental disaster. I read Kerouac as I was writing on California. Jesmyn Ward and Sarah Broom’s writing on loss and disaster helped me situate the experiences of communities like Richmond and Newtok—where colonialism and systemic racism have compounded the impacts of both climate change and, in Richmond’s case, pollution. I also let myself wander into the work of Elinor Ostrom, a political scientist and economist who also wrote about climate change. She became a major character in an essay-style chapter on how we set limits and boundaries on pollution as a society.

I think that kind of research allowed me to make deeper and more organic connections in the book between questions about social and racial justice, economic inequality, and the roots of the climate change—in ways that were nuanced and could reach both people’s intellects and their emotions. That’s part of what art and storytelling do, right? They make surprising connections that force us to look at the world and see it anew. And hopefully in the process, they stir people’s emotions and lead them to action and solutions. That creativity starts with the research process—by letting yourself follow your instincts and your curiosity.

That’s so lovely. Thank you for sharing, Madeline!

And just as a reminder, At Home is for sale wherever you buy books, and comes out in paperback today!

Brilliant! I love the tips and can't wait to read the book!