When the personal is political

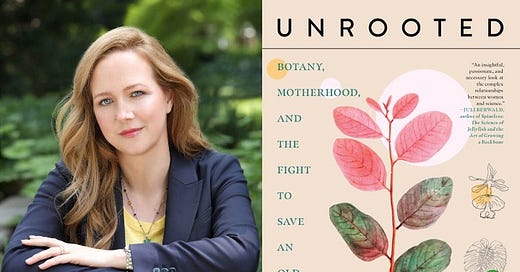

A Q&A with Erin Zimmerman about the "messy and human" project of science

Hi all, happy spring! With the grass growing tall and the flowers going gangbusters, this seems like the perfect time to talk with Erin Zimmerman about her new book, Unrooted: Botany, Motherhood, and the Fight to Save an Old Science (Melville House). Zimmerman trained as a botanist, and the book is partly a memoir of her experience navigating sexism in science. It’s also an examination of how botany itself—which Zimmerman calls a “dying science”—needs women and other historically marginalized scientists more than ever. It’s moving and insightful and available wherever you buy books.

In the following Q&A, we discuss researching things you think you know, writing while parenting, and Zimmerman’s unabashed love of Scrivener.

In the book, you weave back and forth between your story and the science and history of botany. How did research figure into your writing process and what did it look like?

My background in science has left me with an absolute compulsion to cite everything I say, so even with the aspects of botany that were within my own expertise, I tended to research everything for my own peace of mind. And history is not a subject I have any formal background in, so I needed to be conscientious about researching everything carefully. Generally, I used published academic research to learn what I needed, and then used interviews with botanists and historians to double-check my own understanding and build it out further.

I mostly did my research reading ahead of starting to write, but there were plenty of times I needed to stop and jump back into research. The memoir sections of the book were a nice shift in mental gears from the researched parts. When the information started to get overwhelming, I’d switch to a memoir section for a while. I really liked having that option.

I’ve complained here before about how hard it is to find chunks of time for deep research and focused writing when you’re a parent or have other significant non-work obligations. You have kids too. Did you struggle with carving out time to make this book?

Oh boy. Yes, I did. I found this sentence from your newsletter incredibly relatable: “I’ve never needed my cognitive and organizational skills to function more smoothly, and yet, they have never been so compromised by interruption.” I signed my book deal the same month my twins were born (I have two older children as well), so the manuscript got written alongside their infancy and early toddlerhood.

More than anything, I had to learn to write in short bursts and then leave notes for myself to make it quick to pick back up the next time. I also had to get much more comfortable with writing poorly and fixing it later. My process is normally to write very slowly, but produce pretty clean copy the first time that takes minimal editing later on. That wasn’t something I was able to do in a state of exhaustion. I had to just let myself write badly. My first draft was full of square brackets containing sloppy phrasing that I planned to improve later once I’d had some sleep. And a lot of TKs. Anything to just keep the process moving at whatever level of cognition I could bring to it that day.

I relate to that so much—I signed my book contract the day my second child was born. Here’s to “whatever level of cognition” we can each bring to every day!

You write about the science of botany and about historical figures like Charles Darwin and Lydia Becker—a lesser-known but equally fascinating 19th-century scientist. In your experience, how is researching people different than researching science?

I find researching people much more daunting. Understanding someone’s thought processes and motivations alongside the historical context that informs them is incredibly complex. Science is complex, of course, but maybe a bit more clean-cut? Or perhaps I’m just more used to simplifying scientific explanations than explanations of people’s lives.

There’s more interpretation involved in the latter, I think. I was relieved to be able to speak to experts and bounce my impressions off of them to try to see where I might be misunderstanding something. But of course, even the experts disagree sometimes.

I love the botanical illustrations that appear throughout the book—which you made! You explain how the act of drawing plants "requires that I truly see them.” Maybe this is a stretch, but that feels like it could be a metaphor for the book itself. Did researching your own field of study allow you to “truly see” it?

Oooh… great question! Put that way, yes, it did.

Writing about the “big picture” of my own field, both in terms of its history and its current trends, required stepping back and interrogating a lot of things I’d felt personally and assumed to be true about the field, but had never really tried to pin down the truth of before. No one ever sits you down and explains the history and broader trends of your field to you. So in my interviews with senior botanists in particular, there were always several questions that amounted to “am I right to think that this is the situation?” It’s been incredibly satisfying to get this perspective on it all.

As for what I learned… this will sound very silly and naive, but it made me realize that there’s no one in charge. There’s no “World Director of Science” who makes sure that research is always following a logical course and never regresses or backtracks. Science is less unified in the directionality of research than I’d assumed when I was in it, and there are trends where certain methods or interpretations will get fashionable for a while, and then fall out of fashion for not-entirely-objective reasons. There are cliques and trendsetters. The whole enterprise is so messy and human.

What advice would you give others about the research process?

I had what I think of as an information hoarding period before I started to really structure the book. Basically, over a period of a few years (though I don’t think it needs to take that long), I hoarded any and all information that felt even vaguely relevant to the topics or themes I wanted my book to deal with, whether I could see how they would connect or not. I just grabbed and read everything, without trying to direct it or even be efficient about it, and kind of let it all simmer in my head for a while.

I think that unstructured, meandering period of just following my curiosity gave me a better base to work with and helped me to see how all the parts I wanted to include could be assembled in a logical way. My advice would be to give yourself the time to do this, if possible.

Ok, last question. I know you’re on team Scrivener (me too!). What do you like most about it?

I love Scrivener so much. I am, in fact, typing these responses in Scrivener right now. I do all my work there and transfer it to Word only when someone else needs to see it. My research process is to read and mark up pdfs on a tablet screen using an app called PDF Expert, then to import them into Scrivener and view them alongside my document as I’m writing. The split-screen layout is one of my favourite things about this program. That, and the ability to chop documents into tiny chunks and view them individually or in groups. It helps me focus.

The “Collections” function that Scrivener uses to tag documents was very helpful, because it allowed me to assign pdfs to multiple topics according to what they covered. I also put a number of asterisks into the file name of a pdf based on how useful or relevant the information was, as a sort of quick visual reference. I could go on at length about this. Everyone should give it a try if they’re doing long-form writing. (Go, team Scrivener!)

Oh my gosh, the asterisk trick is genius! I love it. This has been wonderful—thank you!

As a reminder you can pick up your copy of Unrooted here. And if you want to hear more from Erin, you can find her on a recent episode of Emerging Form and in Nancy Reddy’s latest good creatures interview, talking creativity and caregiving.